Having just recovered from All Saints' Day, I have decided to share a little about another holiday that occurs in the summer on the most powerful night of the years for doing magic: Saint John's Eve. The following is an essay I wrote about this particular practice while pursuing my masters' degree.

Voodoo in New Orleans is much a solitary practice as compared to the religion in Haiti, but there is an exception: The Feast of Saint John the Baptist.

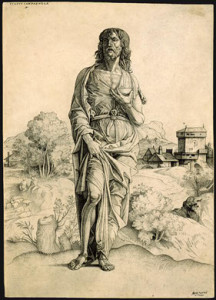

Voodoo in New Orleans is much a solitary practice as compared to the religion in Haiti, but there is an exception: The Feast of Saint John the Baptist, which falls on the 24th of June. The feast day is celebrated in Haiti, and indeed throughout the Catholic world, but nowhere as intensely as in New Orleans. This feast is particularly popular in Francophone countries. In rural France, people light bonfires on Saint John’s Night and in Quebec, on the morning of the feast, an old superstition dictates that one collect drops of dew from leaves and grass to sprinkle around the house for good luck. Also, some believe that when applied to the face, this water will bless a person with a youthful appearance. In New Orleans, the Feast of Saint John is observed most intensely by Voodooists, perhaps as a remnant of a time when it was fêted more fervently by the general population. It is believed that on this night, the veil between the spirit world and the physical world is virtually nonexistent and communion with the ancestors, saints and lwa can be easily achieved. Curiously, a similar belief in the Galicia region of Spain holds that that the souls in Purgatory can return to Earth on that same night, since the mystical dividing veil is lifted. On the eve of Saint John’s Day, every Voodooist is expected to attend a communal drumming session in which members of the local community make food offerings to the ancestors and saints, and this is one of the rare occasions when animal sacrifices, usually chickens, are made by the presiding Voodoo Queen.. All Voodoo queens and doctors, if they are to remain in good standing with the spirits and the local community, are expected to attend a service on this night. The following is a description of the events that occur on this sacred night. The character names are fictitious and represent no persons living of dead, but the details of the ceremony are accurate.

Voodoo in New Orleans is much a solitary practice as compared to the religion in Haiti, but there is an exception: The Feast of Saint John the Baptist, which falls on the 24th of June. The feast day is celebrated in Haiti, and indeed throughout the Catholic world, but nowhere as intensely as in New Orleans. This feast is particularly popular in Francophone countries. In rural France, people light bonfires on Saint John’s Night and in Quebec, on the morning of the feast, an old superstition dictates that one collect drops of dew from leaves and grass to sprinkle around the house for good luck. Also, some believe that when applied to the face, this water will bless a person with a youthful appearance. In New Orleans, the Feast of Saint John is observed most intensely by Voodooists, perhaps as a remnant of a time when it was fêted more fervently by the general population. It is believed that on this night, the veil between the spirit world and the physical world is virtually nonexistent and communion with the ancestors, saints and lwa can be easily achieved. Curiously, a similar belief in the Galicia region of Spain holds that that the souls in Purgatory can return to Earth on that same night, since the mystical dividing veil is lifted. On the eve of Saint John’s Day, every Voodooist is expected to attend a communal drumming session in which members of the local community make food offerings to the ancestors and saints, and this is one of the rare occasions when animal sacrifices, usually chickens, are made by the presiding Voodoo Queen.. All Voodoo queens and doctors, if they are to remain in good standing with the spirits and the local community, are expected to attend a service on this night. The following is a description of the events that occur on this sacred night. The character names are fictitious and represent no persons living of dead, but the details of the ceremony are accurate.

Immediately following Easter, Evangeline carefully plans the sequence of events for the Fête de Saint Jean Baptiste. This year she will serve as presiding priestess over the ceremony, a role to which she was nominated by last year’s mistress of ceremonies, Muriel, her friend and fellow Voodoo Queen. Evangeline contacts all of her friends, family and acquaintances and inquires as to whether she can expect their presence on Saint John’s Eve. In the following weeks, she visits those planning to attend and collects donations to defray the cost of the ceremony. Then she secures a location for the gathering on the Bayou Saint John, where Marie Laveau conducted her infamous ceremonies, and obtains the necessary permits from the city. Then the drummers are hired and Evangeline buys the food and live animals necessary to make offerings to the spirits and to be consumed by the assembly.

The day before the ceremony, Evangeline and two close friends, Renee and Stacey, meet to prepare the food for the following evening. Renee and Stacey prepare such Southern and Creole classics as collard greens and fatback, spoon bread, hopping john, shrimp Creole, dirty rice and pulled pork, all to be consumed by the congregation. Only Evangeline, however, is permitted to prepare the ritual offerings for the spirits. She takes great care to make sure that no a single grain of salt comes into contact with the food offerings. She makes white rice, roasted pork spiced with black and cayenne pepper, grits, and a dish called “amala”, which is a slimly concoctions of chopped okra stewed with corn meal resulting a slippery mess, a taste and texture unappetizing to the human palate, but absolutely decadent to the spirit world. Evangeline thanks her friends and they leave with all the food that has been prepared, and it will be their responsibility to bring the offerings to the gathering the following night. All those expected to attend the service take special herbal baths at home the night before to rid themselves of negativity and neutralize their spiritual vibrations as to be able to fully receive the blessings of the saints and spirits.

On the afternoon of Saint John’s Eve, Evangeline’s friends arrive at the predetermined site and set up the wood pile that will become a massive bonfire. They arrange tables with the previously prepared food as the sacrificial chickens await their imminent death in cages resting on the ground. The drummers arrive shortly after and set up their musical equipment and in the late afternoon the guests start to arrive and socialize while they anticipate the presence of the mistress of ceremonies who is due to arrive at sundown.

When the last amber rays of summer sunlight retreat behind the tree tops, Evangeline arrives. She parks her car a short distance down the street, preferring to make her entrance on foot. Seeing Evangeline in the distance coming toward them, the guests for a semicircle and she takes her place in the center. She stands there for a moment in silence, dressed in white from head to foot resting her weight on the ribbon and bell bedecked baguette des morts. Then, she bangs the stick three times of the ground and makes the opening prayer, “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” The congregation makes the sign of the cross and responds “Amen.” Raising her outstretched palms toward Heaven, she cries, “faith, hope and charity,” the three virtues by which Voodooists are compelled to live. The congregation once again responds with a resounding “Amen” and with that, the ceremony has begun.

Renee and Stacey, Evangeline’s designated helpers from the previous day, come to meet her in the center of the circle. They are to hand her all supplies that she will need throughout the evening. Renee hands her a small vial of holy water that she herself had taken from the baptismal fount at her parish church earlier that day. While Evangeline sprinkles the ground around the soon-to-be ceremonial pyre the congregation softly recites the opening prayers in unison: The Our Father, the Hail Mary and the Apostles’ Creed, in that exact order. Stacey takes Evangeline’s baguette des morts and respectfully holds it while Evangeline tends to the preparation of the fire. The wood having been previously dowsed with kerosene will light without trouble, but Evangeline must first sprinkled the mound with a variety of dried herbs, some graveyard dirt and a few drops of holy water before it is torched. Meanwhile, Renee and Stacey trace a cross in the dirt next to the fire pit using a mixture of cornmeal, ground white eggshells, dust from a church and dirt from a graveyard and a crossroads. When Evangeline finishes consecrating the fire pit, she turns her attention to the cross that Stacey and Renee have prepared. She touches the ground three times and makes the sign of the cross. Then, from a pitcher, she spills water three times on the ground and says “pou mo-ye,” for the dead. Then Renee and Stacey bring her the dishes of food she personally prepared the previous day. With the dishes neatly placed at the four points of the cross, Evangeline declares “mange sec pou mo-ye,” dry eating for the dead. Voodoo pactitioners refer to food offerings as “mange sec” to distinguish them from animal sacrifices in which case the spilt blood is the offering, not the animal itself. The spirits and saints take the offerings of food and spilled blood and convert them into pure energy that is then used to grant their petitions and bring good luck and prosperity into their lives.

With the offerings all laid out, Evangeline takes a sip of rum and then spits in out onto the dirt floor altar in front of her. Then she places a small white taper in each dish of food. When the last taper is lighted, before placing at the center of the cross, Evangeline uses it to set the ceremonial pyre ablaze. The congregation claps and cheers and the drummers begin to play. The rest of the night is a pleasant combination of religious rituals and a friendly party atmosphere. The guests dance and eat traditional Creole specialties as well as drink beer and rum drinks. Throughout the course of the evening, they sing songs in Creole, French and English to call down the saints and ancestors. The spirits make take possession of whomever they choose, not just Evangeline. When a spirit or lwa touches a person and takes control of his body, the drumming stops and the congregation waits in silence for this person to speak. He or she comes forward and speaks to those assembled and gives instructions for spiritual workings to be carried out. The spirit, through the medium, will let the people know if the evil eye or any hexes have been placed on them. If this is found to be true, Evangeline immediately cleanses them of the evil eye or unclean spirits by passing a live chicken over their head and touching it to the palms and backs of their hands. Then, she snaps the chicken’s necks and slits its throat with a sharp knife, squeezing the animal until the last drop of blood is spilled on the ground. The chicken is then disposed of, since it cannot be eaten because the negative influence once on the person has been passed to the chicken.

As the night progresses, more spirits mount the guests and people ask favors of them and lay flowers and dollar bills at their feet to thank them for favors granted in the previous year. This night is one of the few occasions in New Orleans Voodoo where spirit possession takes place, and it is considered an honor to be touched by a spirit. As dawn approaches, Evangeline calls all the guests to the form a circle once again. She calls down her personal spirit guide who indicates the person who is to serve as next years presiding Vooodoo Queen at the fête de Saint Jean Baptiste. It is Stacey. Stacey readily agrees and they seal the new appointment with a kiss on each cheek. Renee retrieves Evangeline’s baguette des morts, which Evangeline once again bangs three times of the ground exclaiming, “faith, hope and charity.” “Amen,” responds the congregation. She strikes three more blows to the earth and prayers, “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” Another magnificent “Amen” rises up from the crowd. They all make the sign of the cross and head for home. The ceremony is over. Only Evangeline remains. She gathers the offerings of food and places them in the center of a cotton cloth, which she then ties up into a neat bundle. She collects the dollar bills strewn about the grounds, which she will donate later that day to a church or charitable organization. As she drives off, she is sure to take a different route than the one she used to get there, as not to let any bad spirits follow her home and ruin her luck. Quickly stopping at a crossroads, she leaves the cloth bundle with the food offerings for the spirits. She drives to her church where Renee and Stacey are waiting for her, and they attend an early morning mass together to celebrate the Feast of Saint John the Baptist.

While Evangeline, Stacey and Renee are fictitious characters, the rituals described in the above story are true and accurate. Other traditions may exist in various communities, since there is no set liturgy as in established churches, but in the Voodoo tradition, the feast of Saint John remains of the most important feasts of the year and is universally observed wherever Voodoo is practiced, be it in Haiti, New Orleans, Martinique or in Afro-Francophone communities in New York and Quebec. Nowhere, however is the tradition more intensely adhered to than in New Orleans. Perhaps this is due to the fact that in Louisiana, as opposed to the other locations mentioned, Francophone Creoles and Voodooists are an ever increasing minority, and the fact that enough people choose to practice this beautiful faith and gather each year to give thanks to God, the ancestors and the saints and be together as a community of believers is cause for celebration. In short, the fact that a people who have been told for centuries by the white Anglo establishment that their culture, language and faith are inferior have been able to hang onto the language spoken by their ancestors who toiled in the cane fields and practice a faith both brought over on slave ships and enriched by the prayers once sung in Latin from high church altars is in and of itself a miracle! The Voodoo faith, like those who profess it, is a Creole religion, and the concept of Creole is simple: A syllogism of drastically different elements melded to form a new and living reality. It is a religion of power and survival.